Pietro Mattioli, 1634, Torpedo Ray and Sea Serpent with Marine Scolopendra

La Torpille (Electric Ray) – recto

Serpent marin (Sea Serpent / Eel) and Scolopendre de mer (Marine Centipede) – verso

Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1501–1578), Les commentaires sur les six livres de Pedacius Dioscoride Anazarbeen, Venice: A. Carbout, 1634

Hand-colored woodcut engraving on laid paper, ~9 × 14 in.

This double-sided folio sheet unites two of the most intriguing themes in Renaissance zoology: the electric ray (torpille), renowned in antiquity for its numbing discharge and used medicinally as a natural “electrotherapy,” and its verso companions, the serpent marin and the fantastical marine scolopendra mythic creatures blending observation of eels and sea worms with the imaginative tradition of Pliny and Aristotle.

The Torpille plate is notable for its circular “electric spots,” a rare early attempt to visualize biological electricity. The verso expands into myth: a coiled eel-like serpent (perhaps conflated with sea dragons) and a many-legged scolopendra said to fall upon fishermen and cause illness. Together, recto and verso embody the Renaissance balance between scientific inquiry and mythical inheritance.

Recto Overview:

Torpedo Ray (Electric Ray)

La Torpille

Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Les commentaires sur les six livres de Pedacius Dioscoride Anazarbeen, Venice: A. Carbout, 1634

Hand-colored woodcut engraving, ~9 × 14 in.Description

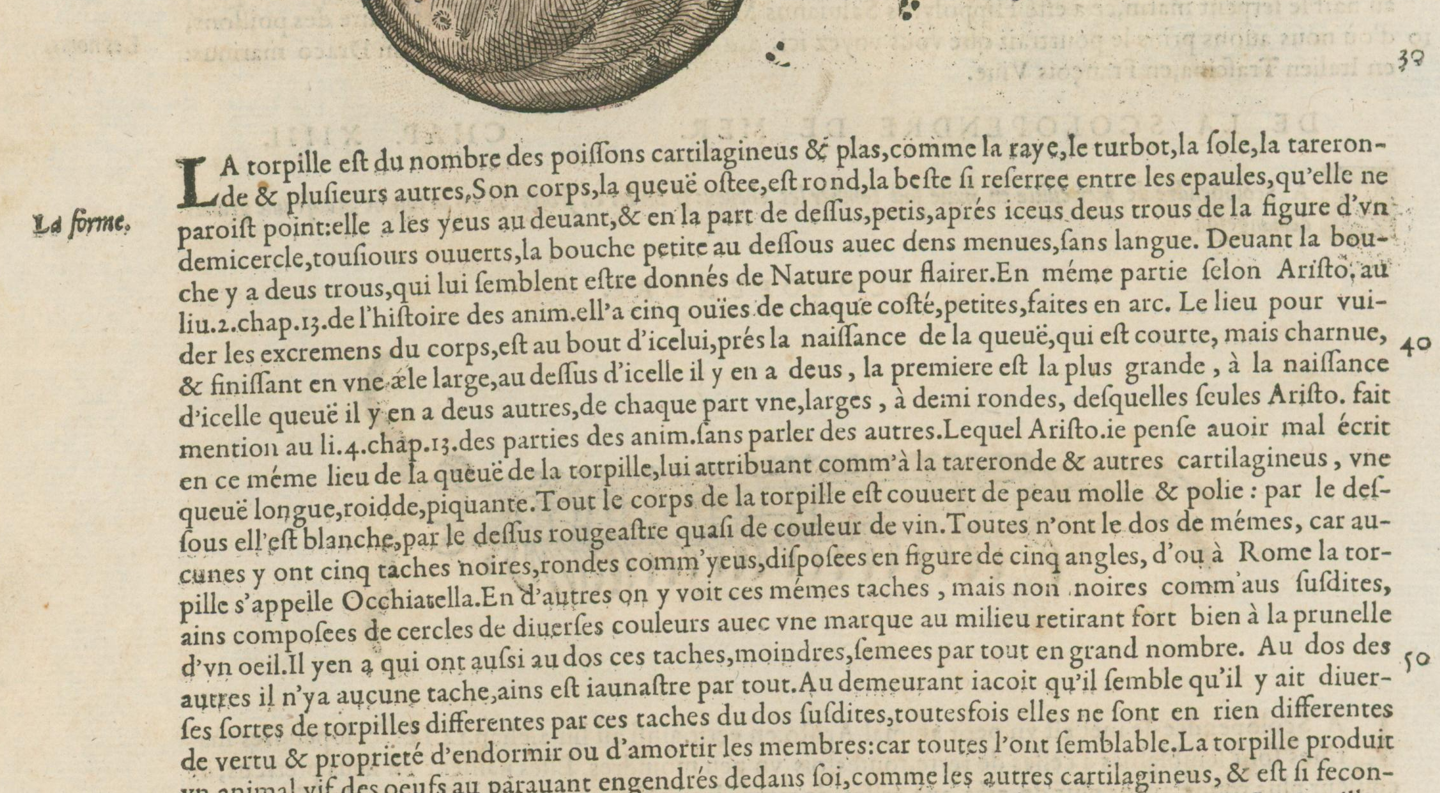

The plate depicts the torpedo ray (Torpedo torpedo), a cartilaginous fish known since antiquity for its numbing electric discharge. Mattioli’s commentary, following Dioscorides and Pliny, highlights the ray’s supposed medicinal powers—its shock believed to ease headaches and toothaches.Translation (excerpt)

“La Torpille de mer appliquée aux douleurs de tête qui ont long temps duré, appaise le subcense du tourment: appliquée aussi au fondement, le fait rentrer dedans & empêche qu’il ne tombe.”

(“The sea torpedo applied to long-lasting headaches eases the burden of torment; applied to the fundament, it prevents prolapse and keeps it from falling out.”)

For the students among us:

The torpedo ray was a central figure in Renaissance natural philosophy, embodying the intersection of myth, medicine, and science. Long before Galvani’s weird frog experiments (1780s) and well before electrotherapy in the 19th century, which is being used right up to today, ancient and Renaissance physicians were already experimenting with the ray’s natural electricity with the term Bio Electricity. A fundamental term that would be at home even today.Pliny the Elder (1st c. AD) wrote that the torpedo could “benumb even at a distance, through the trident of the fisherman.”

Scribonius Largus (Roman physician, c. 47 AD) prescribed a live torpedo applied to the head to cure headaches and migraines.

Galen and later Arabic physicians repeated these traditions, and Mattioli preserves them in the 1634 commentary you have.

The word torpedo itself comes from Latin torpere, “to be numb or paralyzed.” We love this fact!

So in a sense, these early uses of the torpedo ray represent the first recorded form of electrotherapy — over 1,500 years before modern shock treatment. Early naturalists believed its electric discharge a form of divine or occult energy. Compared with Aldrovandi and Rondelet, Mattioli’s depiction is strikingly anatomical, with circular “electric spots” engraved. So if you think about a few young Egyptian fishermen out on the Nile of a sunny morning hearing the sudden shriek of his compatriot after being struck by a Torpedo, little did they know that the shock and numbness that this amazing creature produced would still be talked about two thousand years later.

Rarity & Provenance

Plates from Mattioli’s 1634 French edition remain scarce on the market. Many institutionalised; surviving hand-colored impressions are rarer still.

Verso Overview:

Serpent marin (Sea Serpent / Eel) and Scolopendre de mer (Marine Centipede)

The verso of this sheet presents two of the most fascinating survivals of Renaissance natural history’s interplay with myth and medicine. At the top is the Serpent marin, a coiled eel-like creature described as both a natural eel and a marine dragon (draco marinus) — a hybrid that reflects Aristotle’s and Pliny’s accounts of monstrous sea serpents caught by fishermen. This image embodies the enduring cultural fear of serpents in the ocean, positioned at the threshold between empirical zoology and medieval bestiary lore.

Beneath it lies the Scolopendre de mer, a long, many-legged marine centipede, believed in antiquity to live among coastal rocks and to afflict fishermen with poisonous bites. Rondelet and other naturalists attempted to rationalise these accounts, but the form retains a clearly mythical aura. For Mattioli’s audience, such engravings illustrated the dangers of the sea as much as its bounty.

Rarity & Appeal

The verso content adds exceptional depth to the Torpille recto. While the electric ray is scientifically pivotal, the verso amplifies the leaf’s allure for collectors interested in sea monsters, mythology, and the blurred boundary between science and imagination.This combination significantly increases desirability compared with single-side botanical or zoological sheets from Mattioli.

The background to this document:

So, just in case you haven’t had enough of this electrifying document, here is the timeline of the creation of the original De Materia Medica in the first century through to you holding the print in your hand once you buy it!

1st century AD — Dioscorides composes De Materia Medica, a pharmacological manual describing ~600 plants, animals, and minerals with medicinal uses.

512 AD — The Vienna Dioscorides (Byzantine illuminated manuscript) is created for Princess Anicia Juliana, preserving the text in Greek with lavish illustrations.

9th–10th centuries — De Materia Medica translated into Arabic; widely circulated in the Islamic world with commentaries that later re-enter Europe.

1478 — First printed Latin edition of De Materia Medica (Colle, Italy), bringing the text into Renaissance print culture.

1544 — Pietro Andrea Mattioli publishes his Italian commentary, expanding Dioscorides with Alpine plants, zoological notes, and contemporary medical practice.

1554 — Mattioli issues a Latin edition with hundreds of woodcut illustrations, transforming the work into a Renaissance natural history encyclopedia.

1634 — French edition, Venice (published posthumously by A. Carbout), continuing Mattioli’s influence across Europe.

2025 - You log onto Lumenrare and see this wonderful work, buy it, receive the document in its sealed container by courier, you hold it with the cotton gloves you just bought, you give it a smell and then you dig a hole in your garden and put it in a time capsule for a scientific student to find in another five hundred years.

La Torpille (Electric Ray) – recto

Serpent marin (Sea Serpent / Eel) and Scolopendre de mer (Marine Centipede) – verso

Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1501–1578), Les commentaires sur les six livres de Pedacius Dioscoride Anazarbeen, Venice: A. Carbout, 1634

Hand-colored woodcut engraving on laid paper, ~9 × 14 in.

This double-sided folio sheet unites two of the most intriguing themes in Renaissance zoology: the electric ray (torpille), renowned in antiquity for its numbing discharge and used medicinally as a natural “electrotherapy,” and its verso companions, the serpent marin and the fantastical marine scolopendra mythic creatures blending observation of eels and sea worms with the imaginative tradition of Pliny and Aristotle.

The Torpille plate is notable for its circular “electric spots,” a rare early attempt to visualize biological electricity. The verso expands into myth: a coiled eel-like serpent (perhaps conflated with sea dragons) and a many-legged scolopendra said to fall upon fishermen and cause illness. Together, recto and verso embody the Renaissance balance between scientific inquiry and mythical inheritance.

Recto Overview:

Torpedo Ray (Electric Ray)

La Torpille

Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Les commentaires sur les six livres de Pedacius Dioscoride Anazarbeen, Venice: A. Carbout, 1634

Hand-colored woodcut engraving, ~9 × 14 in.Description

The plate depicts the torpedo ray (Torpedo torpedo), a cartilaginous fish known since antiquity for its numbing electric discharge. Mattioli’s commentary, following Dioscorides and Pliny, highlights the ray’s supposed medicinal powers—its shock believed to ease headaches and toothaches.Translation (excerpt)

“La Torpille de mer appliquée aux douleurs de tête qui ont long temps duré, appaise le subcense du tourment: appliquée aussi au fondement, le fait rentrer dedans & empêche qu’il ne tombe.”

(“The sea torpedo applied to long-lasting headaches eases the burden of torment; applied to the fundament, it prevents prolapse and keeps it from falling out.”)

For the students among us:

The torpedo ray was a central figure in Renaissance natural philosophy, embodying the intersection of myth, medicine, and science. Long before Galvani’s weird frog experiments (1780s) and well before electrotherapy in the 19th century, which is being used right up to today, ancient and Renaissance physicians were already experimenting with the ray’s natural electricity with the term Bio Electricity. A fundamental term that would be at home even today.Pliny the Elder (1st c. AD) wrote that the torpedo could “benumb even at a distance, through the trident of the fisherman.”

Scribonius Largus (Roman physician, c. 47 AD) prescribed a live torpedo applied to the head to cure headaches and migraines.

Galen and later Arabic physicians repeated these traditions, and Mattioli preserves them in the 1634 commentary you have.

The word torpedo itself comes from Latin torpere, “to be numb or paralyzed.” We love this fact!

So in a sense, these early uses of the torpedo ray represent the first recorded form of electrotherapy — over 1,500 years before modern shock treatment. Early naturalists believed its electric discharge a form of divine or occult energy. Compared with Aldrovandi and Rondelet, Mattioli’s depiction is strikingly anatomical, with circular “electric spots” engraved. So if you think about a few young Egyptian fishermen out on the Nile of a sunny morning hearing the sudden shriek of his compatriot after being struck by a Torpedo, little did they know that the shock and numbness that this amazing creature produced would still be talked about two thousand years later.

Rarity & Provenance

Plates from Mattioli’s 1634 French edition remain scarce on the market. Many institutionalised; surviving hand-colored impressions are rarer still.

Verso Overview:

Serpent marin (Sea Serpent / Eel) and Scolopendre de mer (Marine Centipede)

The verso of this sheet presents two of the most fascinating survivals of Renaissance natural history’s interplay with myth and medicine. At the top is the Serpent marin, a coiled eel-like creature described as both a natural eel and a marine dragon (draco marinus) — a hybrid that reflects Aristotle’s and Pliny’s accounts of monstrous sea serpents caught by fishermen. This image embodies the enduring cultural fear of serpents in the ocean, positioned at the threshold between empirical zoology and medieval bestiary lore.

Beneath it lies the Scolopendre de mer, a long, many-legged marine centipede, believed in antiquity to live among coastal rocks and to afflict fishermen with poisonous bites. Rondelet and other naturalists attempted to rationalise these accounts, but the form retains a clearly mythical aura. For Mattioli’s audience, such engravings illustrated the dangers of the sea as much as its bounty.

Rarity & Appeal

The verso content adds exceptional depth to the Torpille recto. While the electric ray is scientifically pivotal, the verso amplifies the leaf’s allure for collectors interested in sea monsters, mythology, and the blurred boundary between science and imagination.This combination significantly increases desirability compared with single-side botanical or zoological sheets from Mattioli.

The background to this document:

So, just in case you haven’t had enough of this electrifying document, here is the timeline of the creation of the original De Materia Medica in the first century through to you holding the print in your hand once you buy it!

1st century AD — Dioscorides composes De Materia Medica, a pharmacological manual describing ~600 plants, animals, and minerals with medicinal uses.

512 AD — The Vienna Dioscorides (Byzantine illuminated manuscript) is created for Princess Anicia Juliana, preserving the text in Greek with lavish illustrations.

9th–10th centuries — De Materia Medica translated into Arabic; widely circulated in the Islamic world with commentaries that later re-enter Europe.

1478 — First printed Latin edition of De Materia Medica (Colle, Italy), bringing the text into Renaissance print culture.

1544 — Pietro Andrea Mattioli publishes his Italian commentary, expanding Dioscorides with Alpine plants, zoological notes, and contemporary medical practice.

1554 — Mattioli issues a Latin edition with hundreds of woodcut illustrations, transforming the work into a Renaissance natural history encyclopedia.

1634 — French edition, Venice (published posthumously by A. Carbout), continuing Mattioli’s influence across Europe.

2025 - You log onto Lumenrare and see this wonderful work, buy it, receive the document in its sealed container by courier, you hold it with the cotton gloves you just bought, you give it a smell and then you dig a hole in your garden and put it in a time capsule for a scientific student to find in another five hundred years.