Pietro Mattioli, 1634, Marine Hare, Stingray, and Squid

Lepus marinus, Tareronde, Seiche

Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1501–1577), Commentarii on Dioscorides, French edition, Venice, A. Carbout, 1634.

Woodcuts on laid paper, folio.

This leaf is from the rare 1634 French edition of Pietro Andrea Mattioli’s Commentarii on Dioscorides, printed in Venice by A. Carbout. Although Mattioli originally composed his commentary in Italian and later issued Latin editions, his work was translated into French—likely in the mid-16th century in Lyon—to reach a broader audience of physicians and apothecaries. The 1634 reprint preserves that French text, but the identity of the translator remains unknown in surviving records. Because the French edition is less documented and less widely held than the Latin or Italian versions, complete recto–verso leaves from this issue are especially scarce and treasured by collectors.

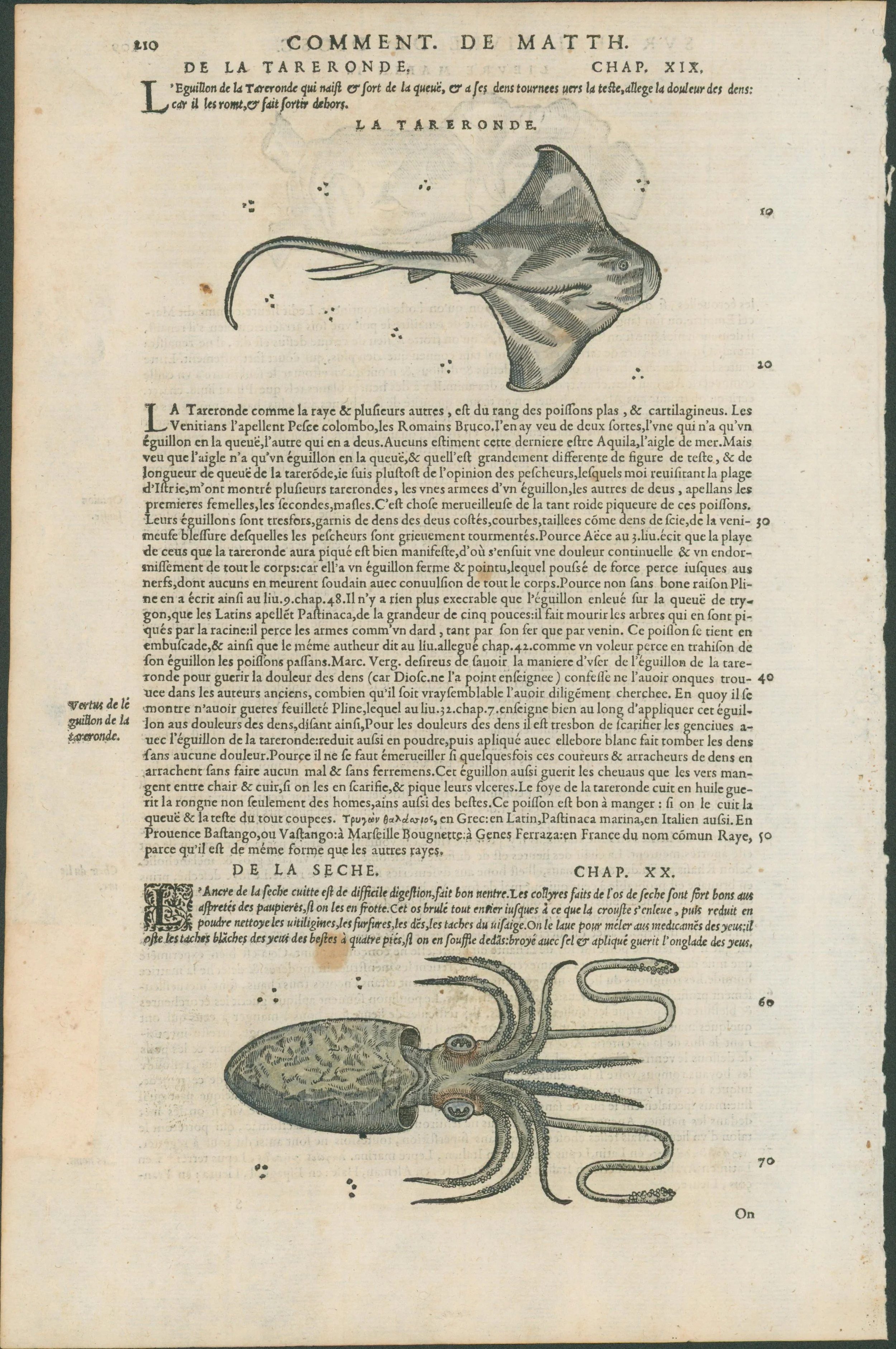

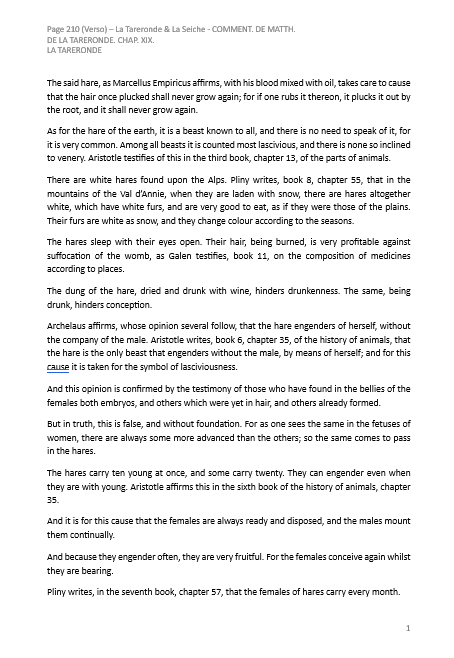

This striking recto–verso leaf juxtaposes three of the most unusual marine creatures in Dioscoridean natural history. On the recto (p. 209) appears the marine hare (Lepus marinus), a fantastical zoological form described as half–fish, half–hare, thought to embody medicinal and magical properties. On the verso (p. 210) are two important illustrations: the stingray (Tareronde), with its venomous tail spine described by Pliny and Oppian, and the squid (Seiche), one of the earliest printed cephalopod depictions.

Compared with Mattioli’s more common botanical pages, these marine zoological subjects are far rarer on the market. The marine hare reflects the Renaissance fascination with hybrid sea-monsters, bridging natural history and mythology. The stingray is notable for early recognition of its toxic sting, still accurate zoologically. The squid engraving, with curling tentacles and bulbous head, anticipates 17th–18th century cephalopod studies.

Mattioli notes that the stingray (Tareronde) was called Pesce colombo in Venice and Bruco in Rome. While bruco normally means “caterpillar” in Italian, there is no classical or modern source linking the word to rays — Dioscorides himself used the Greek narkē. This suggests Mattioli was recording a local Roman fishermen’s term, now otherwise lost, offering a rare glimpse into Renaissance vernacular taxonomy.

Leaves with composite marine subjects (mythical + zoological) appear less frequently than crustaceans or molluscs. French edition (Venice, 1634) examples are particularly scarce, underrepresented in institutional holdings compared to Latin/Italian versions.

The background to this document:

So, just in case you haven’t had enough of this fishy document, here is the timeline of the creation of the original De Materia Medica in the first century through to you holding the print Mattioli intended you to have in your hand,

1st century AD — Dioscorides composes De Materia Medica, a pharmacological manual describing ~600 plants, animals, and minerals with medicinal uses.

512 AD — The Vienna Dioscorides (Byzantine illuminated manuscript) is created for Princess Anicia Juliana, preserving the text in Greek with lavish illustrations.

9th–10th centuries — De Materia Medica translated into Arabic; widely circulated in the Islamic world with commentaries that later re-enter Europe.

1478 — First printed Latin edition of De Materia Medica (Colle, Italy), bringing the text into Renaissance print culture.

1544 — Pietro Andrea Mattioli publishes his Italian commentary, expanding Dioscorides with Alpine plants, zoological notes, and contemporary medical practice.

1554 — Mattioli issues a Latin edition with hundreds of woodcut illustrations, transforming the work into a Renaissance natural history encyclopedia.

1634 — French edition, Venice (published posthumously by A. Carbout), continuing Mattioli’s influence across Europe.

2025 - You log onto Lumenrare and see this wonderful work, buy it, receive the document in its sealed container by courier, you hold it with the cotton gloves you just bought, you give it a smell and then you dig a hole in your garden and put it in a time capsule for a scientific student to find in another five hundred years.

Lepus marinus, Tareronde, Seiche

Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1501–1577), Commentarii on Dioscorides, French edition, Venice, A. Carbout, 1634.

Woodcuts on laid paper, folio.

This leaf is from the rare 1634 French edition of Pietro Andrea Mattioli’s Commentarii on Dioscorides, printed in Venice by A. Carbout. Although Mattioli originally composed his commentary in Italian and later issued Latin editions, his work was translated into French—likely in the mid-16th century in Lyon—to reach a broader audience of physicians and apothecaries. The 1634 reprint preserves that French text, but the identity of the translator remains unknown in surviving records. Because the French edition is less documented and less widely held than the Latin or Italian versions, complete recto–verso leaves from this issue are especially scarce and treasured by collectors.

This striking recto–verso leaf juxtaposes three of the most unusual marine creatures in Dioscoridean natural history. On the recto (p. 209) appears the marine hare (Lepus marinus), a fantastical zoological form described as half–fish, half–hare, thought to embody medicinal and magical properties. On the verso (p. 210) are two important illustrations: the stingray (Tareronde), with its venomous tail spine described by Pliny and Oppian, and the squid (Seiche), one of the earliest printed cephalopod depictions.

Compared with Mattioli’s more common botanical pages, these marine zoological subjects are far rarer on the market. The marine hare reflects the Renaissance fascination with hybrid sea-monsters, bridging natural history and mythology. The stingray is notable for early recognition of its toxic sting, still accurate zoologically. The squid engraving, with curling tentacles and bulbous head, anticipates 17th–18th century cephalopod studies.

Mattioli notes that the stingray (Tareronde) was called Pesce colombo in Venice and Bruco in Rome. While bruco normally means “caterpillar” in Italian, there is no classical or modern source linking the word to rays — Dioscorides himself used the Greek narkē. This suggests Mattioli was recording a local Roman fishermen’s term, now otherwise lost, offering a rare glimpse into Renaissance vernacular taxonomy.

Leaves with composite marine subjects (mythical + zoological) appear less frequently than crustaceans or molluscs. French edition (Venice, 1634) examples are particularly scarce, underrepresented in institutional holdings compared to Latin/Italian versions.

The background to this document:

So, just in case you haven’t had enough of this fishy document, here is the timeline of the creation of the original De Materia Medica in the first century through to you holding the print Mattioli intended you to have in your hand,

1st century AD — Dioscorides composes De Materia Medica, a pharmacological manual describing ~600 plants, animals, and minerals with medicinal uses.

512 AD — The Vienna Dioscorides (Byzantine illuminated manuscript) is created for Princess Anicia Juliana, preserving the text in Greek with lavish illustrations.

9th–10th centuries — De Materia Medica translated into Arabic; widely circulated in the Islamic world with commentaries that later re-enter Europe.

1478 — First printed Latin edition of De Materia Medica (Colle, Italy), bringing the text into Renaissance print culture.

1544 — Pietro Andrea Mattioli publishes his Italian commentary, expanding Dioscorides with Alpine plants, zoological notes, and contemporary medical practice.

1554 — Mattioli issues a Latin edition with hundreds of woodcut illustrations, transforming the work into a Renaissance natural history encyclopedia.

1634 — French edition, Venice (published posthumously by A. Carbout), continuing Mattioli’s influence across Europe.

2025 - You log onto Lumenrare and see this wonderful work, buy it, receive the document in its sealed container by courier, you hold it with the cotton gloves you just bought, you give it a smell and then you dig a hole in your garden and put it in a time capsule for a scientific student to find in another five hundred years.