The Naturalist’s Miscellany, an 18th century journal

The Naturalist’s Miscellany, published between 1789 and 1813, was one of the first illustrated natural history journals to appear as a monthly subscription. It was, in many ways, the eighteenth-century equivalent of National Geographic. Each issue contained one or two hand-coloured engravings and an accompanying text page, posted directly to subscribers who would later bind the numbers into volumes. Because of this practice, no two surviving sets are identical. The colouring, paper tone, and even the sequence of plates often vary depending on who assembled them. Many were coloured by hand in the Nodder family studio, and each bears slight individual differences that make every surviving plate a unique early print of scientific art.

When it was first issued, the subscription price was one shilling and sixpence per number—a modest sum in appearance, but a meaningful investment for the time. A skilled tradesman earned around twelve to eighteen shillings per week, while a labourer might make six to nine. Middle-class professionals such as doctors, clergymen, or government clerks earned between £150 and £300 per year, and a gentleman of independent means might live on £500 or more. The cost of each issue therefore represented roughly a day’s pay for a craftsman, or one-tenth to one-quarter of a weekly labourer’s income. Maintaining the subscription over two decades amounted to nearly twenty pounds in total—equivalent to a year’s rent for a modest London house, or several months of professional wages. In today’s money, this would equal around two to three thousand pounds.

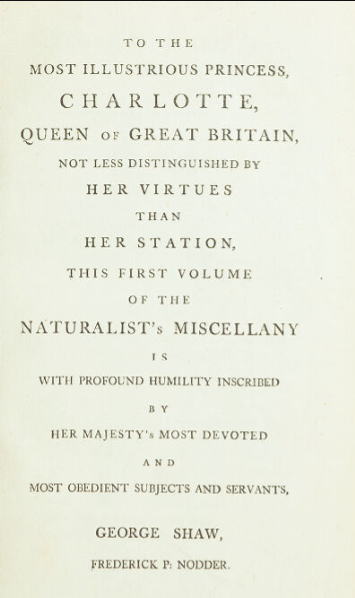

This pricing placed The Naturalist’s Miscellany firmly in the realm of educated affluence. Its subscribers were gentlemen naturalists, physicians, clergymen, and colonial officers fascinated by the expanding world of exotic species; educated women who collected the beautifully coloured plates as refined decoration and conversation pieces; and major institutions such as the British Museum and the Linnean Society, which valued George Shaw’s access to new specimens arriving from across the Empire.

Because each part was sold loose and privately bound, uniform complete sets are rare today. Individual plates—especially those that retain the descriptive text leaf—carry with them the intimate history of Enlightenment collecting: a moment when scientific curiosity, aesthetic pleasure, and the commerce of print intertwined to bring the natural world into the drawing rooms of Europe.